It is two decades since the Pharmaceutical Contract Management Group (PCMG) first highlighted how the approach to outsourcing of the biopharmaceutical industry compared to others, such as IT, automotive, or construction. It concluded that pharma was at least 10 years behind in terms of maturity, vendor relationships, contracting and pricing. Subsequent developments have seen these industries evolve further; entering the age of third generation outsourcing models adopted as standard across multiple business sectors.

There has been no similar revolution in pharma sourcing, which has remained remarkably static; preferring to recycle dated models over embracing innovation and change. These tried and tested models have unsurprisingly failed to deliver the levels of service, quality or timelines for delivery. After a generation of moving delivery systems to service companies, sponsor companies are now looking to “bring more services back in house”, “take control of the day-to-day activities of their CROs” and introduce “mechanisms to hold CROs to account for their promises and failure to deliver”. This feels like a step back rather than positive evolution and raises the question of why this trend is occurring.

Despite best efforts on both sides) the “Master & Servant” approach is still highly pervasive. Both parties are vocal about the lack of trust, Sponsors around the failure of CROs to deliver on their promises, and CROs on the desire of Sponsors to create true partnerships.

Sponsors are continuing to apply a more “Procurement” approach to clinical sourcing, which prioritises cost savings over operational fit and effectiveness i.e. price over value. Termed as a “race to the bottom”, this position greatly undervalues the contributions made by the highly knowledgeable and experienced professionals employed by service providers.

Applied Clinical Trials recently published an article reporting the key findings of a survey conducted by OCT Clinical that was completed by 320 industry experts from both Sponsors and CROs [1]. The survey, looking at efficient collaboration, highlighted age-old issues and grievances held by both sides. The most disappointing observation was that the specific findings and quotes from respondents could easily have been taken from ten, fifteen or twenty years ago. Despite countless documented delivery failures, the industry has continued with its expansion of the outsourcing approach with little consideration around lessons learned.

At the DIA conference in 2017, it was reported that approximately 80% of trials were failing to meet timelines irrespective of the resourcing model employed by the Sponsor company. There has been little evidence since to suggest this has changed[2]. Irrespective of the source of these failures the impact has been to put ever-increasing strain on the perception of trust.

Relationship Management

Over recent years the industry has invested significantly in vendor and relationship management, alongside governance and escalation processes, yet attitudes between the parties remain largely unchanged. Given the importance of trust in achieving any shared undertaking it would be worthwhile exploring the specifics of how we build (or destroy) trust, particularly in our industry.

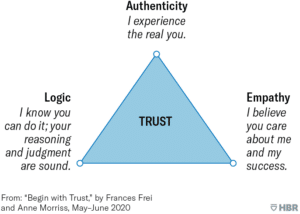

In the Harvard Business Review Frances Frei and Anne Morriss outlined three core drivers of trust – authenticity, empathy and logic. They stated that a breakdown in at least one of these drivers can be identified as the cause of mistrust in almost all cases. [3]

They characterised the drivers within The Trust Triangle [3] .

It is clear that the biopharma and service provider industries have performed badly across all three dimensions. At a trial level there are, obviously some great success stories; individuals themselves can, and do, have great working relationships with their counterparts on either side of the relationship. However, the prevailing sense at a macro level is one of deep distrust.

Exploring each driver in turn and examining trends in behaviours and attitudes from both parties clearly demonstrates these failings. Some common observations include:

Authenticity:

- CROs often tell Sponsors what they want to hear not what they need to hear.

- Sponsors are not prepared to listen to CRO guidance and feedback or don’t act in a timely or appropriate manner on the advice.

Empathy:

- Sponsor and CROs have differing priorities which are not well acknowledged and understood.

- Competing pressures mean there is little shared ownership and collective commitment to delivery.

- Sponsors striving for greater “control” without comprehending the impact of excessive oversight and metric gathering on the engagement of CRO teams.

Logic:

- Despite continued failure to meet expectations, Sponsor teams are not yet adopting a sufficiently pragmatic approach to assessing proposed timelines and costs.

- The details that Sponsors provide CROs to generate proposals are not sufficient to give an accurate projection of total effort, cost and timelines.

Experience, supporting a number of clinical teams across multiple Sponsors, points to a handful of key mistrust axis points, such as:

- Sponsor teams openly saying they are “looking for the least bad CRO” at the selection stage; implying that there are no CROs who can actually deliver as required.

- Sponsor teams actively handicapping the CRO during trial delivery to provide a scapegoat for predicted failures to meet timelines.

- CRO teams spending more time covering up errors, completing reports and measuring progress than actually progressing the trial.

The current situation is well summarised in the book Let’s Get Real or Let’s Not Play, which says:

“When buyers do not trust sellers, they hide and protect vital information and restrict personal contact. Sellers have to guess what would actually work for the client, and often guess wrong. This reinforces the perception that sellers can’t be trusted, and dissatisfied buyers then create bigger hurdles. Sellers acquiesce and either go along with things that do not make sense…or chose to withdraw.” [4]

These behaviours are being played out firsthand with some suppliers seriously considering whether to respond to RFPs, informing Sponsors that they do not want to be considered for any of their future trials, based on prior experiences.

Given the extreme pressure on the pharma industry to increase productivity, reduce the time to market and slash development costs, the race is on to find a new approach.

The only sensible course of action is to address these behaviours and learn from the successes of other industries.

Balance of Power

The market for R&D service providers is considered to be healthy, as evidenced by the scale of private equity investment and the market performance for publicly traded companies (see table below)

Market cap of four publicly traded CROs: [5]

| 28th Feb 2019

(US $) |

4th March 2024

(US $) |

% Change | |

| IQVIA Holdings Inc. | 27.71 B | 45.93 B | 66% |

| ICON PLC | 7.56 B | 27.05 B | 258% |

| Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (PPD) | 103.57 B | 202.96 B | 113% |

| Medpace Holdings Inc. | 1.96 B | 12.39 B | 532% |

The future financial predictions continue to be favourable, with the global CRO services market projected to be approximately US $82B in 2024, reaching around US $130B by 2029.

However, the market is dominated by a small number of full service global CROs, delivering services in a broadly similar manner.

A number of things can be inferred from these facts:

- Sponsor companies have limited options when outsourcing large-scale clinical trials.

- Large full-service CROs have the financial backing to acquire smaller competitors and providers of new services into their organisations.

- Choice for “supporting services”, or for creating collaborative networks across suppliers, is limited as key suppliers are unwilling to work with their competitors.

- Sponsors need to make long-term commitments to high-value contracts. The average duration of a Phase II clinical trial is around 18 months and around 3 years for a Phase III trial.

- Models and processes for delivering trials are well established and highly regulated reducing the threat of substitute products entering the market.

Porter’s 5 Forces model would suggest that the balance of power in the relationship between Sponsor and CRO sits firmly with the CRO, particularly during the course of an ongoing study. It is well recognised that it is very costly to move a trial from one CRO to another during the delivery of that trial. Not only the potential impact on the total cost and the overall timelines, but there is also a risk to data quality and integrity. For these reasons Sponsors are very reticent to take this course of action, reserving it for only the most serious of cases.

Any new outsourcing model must lower the threshold to change suppliers in terms of impact on the trial delivery. The model must also have mechanisms to reward collaborative working across a network of suppliers. This would significantly rebalance the power in favour of the Sponsor.

The Larger Macroeconomic Climate

The observations outlined above touch on key issues that impact clinical development and sourcing professionals at the coal face of trial delivery. However, the larger macroeconomic pressures should also be factored in when considering the need for a new outsourcing model.

The cost to develop a new drug has been increasing steadily, as has the pressure from payors to control and reduce the cost of approved treatments. The significant spike in global inflation rates and the introduction of legislation around the world, most notably the Inflation Reduction Act in USA, has brought into stark relief the need to find ways to bring drugs to the market more quickly, efficiently and at a lower cost.

These extreme pressures are being felt at all levels across R&D. Conversations 4C Associates has had with industry professionals within biopharma companies of all sizes as well as at CROs demonstrated a consistent theme. All companies are searching for improvements which must deliver marked reductions in the time to achieve key milestones and reduce the overall price of clinical development. Though it was observed that very few real disruptive innovations are being considered and the primary approach has been to exert greater pressure on service providers though existing models.

The Cellular Services Model

Taking learnings from successful industry sectors that have implemented innovative sourcing strategies, and achieved paradigm shifts in delivery efficiency, 4C Associates has been developing a new approach that is based on other complex Business Process Outsourcing models. Our model introduces mechanisms that provide the necessary flexibility to bring in best-in-class suppliers across different functions and disciplines. It incorporates structures to improve performance levels across a complex ecosystem of suppliers. We call this the Cellular Services Model. In other industries, approaches of this kind delivered efficiencies of up to 40%.

Get in touch with Rob Aitchison if you would like to join the conversation and contribute to introducing a new approach to clinical outsourcing in your organisation. Rob is Head of R&D Outsourcing Advisory within the Life Sciences practice at 4C Associates. He has over 25 years of experience within the pharmaceutical industry, primarily focused on R&D outsourcing and business-to-business relationship management.

References

[1] Applied Clinical Trials, 18th May 2022, “What Stands in the Way of an Efficient CRO-Pharma Collaboration?”, Ekaterina Bulaeva & Amalia Iljasova.

[2] NIH National Library of Medicine, 4 Nov 2020, “Online Patient Recruitment in Clinical Trials: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”, Mette Brøgger-Mikkelsen, Zarqa Ali, John R Zibert, Anders Daniel Andersen, Simon Francis Thomsen.

[3] Harvard Business Review, May-June 2020 “Begin with Trust”, Frances Frei & Anne Morriss.

[4] “Lets Get Real or Lets Not Play”, Mahan Khalsa & Randy Illig.